Addressing Rural Electrification with Microsolar

How green loans bring light to areas off the grid

Originally posted on March 6, 2010

In an earlier post, I talked about green products and the concept of the triple bottom line. Environmental cookstoves save money, save lives, and produce less carbon emissions. Believe it or not, black carbon, or soot from cookstoves in developing countries, is the number-two contributor to global warming. These more efficient stoves pay dividends. But this is not the only green product serving the developing world. Solar products – lanterns, cell-phone charging stations, DVD players, and even micro-utilities – offer a cheap, alternative means of energy delivery in the third world.

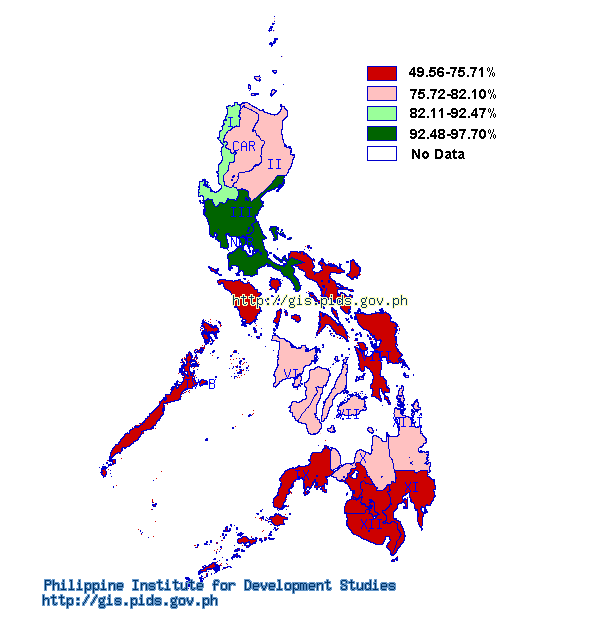

One major problem for the poor is a lack of electricity. Across the globe, 1.5 billion people – a quarter of the world population – do not have access to electricity. In the Philippines, where I live, the electric grid fails to reach many rural communities, where the bulk of the poor reside. The major utilities divide the territories and control the delivery of electricity in the country. When a community is too remote to be economically viable, the utility may choose not to electrify to the area, leaving the job to the government. Rural Electric Cooperatives (RECs) assume the responsibility, but do not reach everyone. Just looking at the map shown above you see the vast area of the Philippines that are less than 75% electrified. The vast areas of red – the island of Palawan to the west and Mindanao to the south – represent the regions where population density is sufficiently low or the areas are too poor to justify access to the energy grid. Here, the cost of building the infrastructure – wires, electricity poles, transformers, etc. – makes the process cost-prohibitive. So, you need to develop another strategy.

One solution to this problem is something called distributed generation, better known as an “off the grid” solution. Here is a brief description:

Distributed energy resource (DER) systems are small-scale power generation technologies (typically in the range of 3 kW to 10,000 kW) used to provide an alternative to or an enhancement of the traditional electric power system.

Distributed energy takes many forms – hydroelectric, solar, wind (excluding large power plants). These DER systems tend to be large enough to power at least a home (via a generator) or sometimes a community. Then there are even smaller applications, which light the home or serve as a single outlet for charging a phone. Negros Women for Tomorrow Foundation (NWTF) is in the process of rolling out a pilot program to distribute solar lanterns to its clients. The purchase is funded through an asset acquisition loan. It costs about $70 USD and the loan cycle is either one or two years. How do solar lanterns serve the triple bottom line? I’m glad you asked.

When a rural community has no electricity, it does not mean that nighttime means total darkness. Traditional lanterns run on kerosene, which needs to be purchased in large amounts to light a community. In contrast, solar lanterns use the free energy offered by the sun, eliminating the need to purchase kerosene. This saves the user big dollars in the long-run, particularly when the battery for a solar lantern lasts up to 3-4 years. The lanterns distributed by NWTF have three settings: high (2 hours), medium (8 hours), and low (200 hours). Reducing kerosene expenses means lights can be kept on longer. This means the store can stay open longer, the kids can study at night, and businesses are more profitable. The impact on a household and the community at-large is dramatic.

There are hundreds of organizations serving this market, trying to scale it up to a level that will reach the billions without electricity. Grameen Bank, Muhammad Yunus’ flagship microfinance organization, has a subsidiary called Grameen Shakti that focuses delivering solar energy (among other green things) to the poor in Bangladesh. The description of the program also offers a nice summary of the benefits:

Rural electrification through solar PV technology is becoming more popular, day by day in Bangladesh. Solar Home Systems (SHSs) are highly decentralized and particularly suitable for remote, inaccessible areas. GS’s solar program mainly targets those areas, which have no access to conventional electricity and little chance of getting connected to the grid within 5 to 10 years. It is one of its most successful programs. Currently, GS is one of the largest and fastest growing rural based renewable energy companies in the world. GS is also promoting Small Solar Home System to reach low income rural households.

SHSs can be used to light up homes, shops, fishing boats etc. It can also be used to charge cellular phones, run televisions, radios and cassette players. SHSs have become increasingly popular among users because they present an attractive alternative to conventional electricity such as no monthly bills, no fuel cost, very little repair, maintenance costs, easy to install any where etc.

But there are challenges in distributing these products to clients. For one thing, microfinance institutions are, above all else, lenders. MFIs are in the business of extending credit loans to the unbanked and are often ill-equipped to deal with the technical aspects of distributing solar lanterns. Fortunately, the manufacturers take this into account and place a premium on building durable products with minimal maintenance required. But some organizations are specialists, like Grameen Shakti. It is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Grameen Bank that focuses exclusively on solar. GS technicians install the product and service the warranty. At institutions without the same depth of expertise, that task is left to a loan officer with some training. There are different ways of solving this problem, usually involving some sort of partnership between the MFI, the manufacturer, and the distributor. In the case of the Philippines, there are partner companies that re responsible for distributing and servicing the products.

This is a good solution to an overlooked problem – the dismal electrification rate in some parts of the developing world. It is an example of the good work that MFIs can do beyond just providing credit.

Update:

April 23 – Today I have the pleasure of announcing that Negros Women for Tomorrow Foundation has begun posting loans for renewable energy products on Kiva.